What is art if not the perpetual pursuit of utopia? Artists and designers translate their passion for their craft into prototypes that reveal an ambitious vision of mediums—proposing time and gaining new perspectives on the world. Moreover, artistic manifestations bring with them a much-needed pause, ensnaring the onlookers and ushering their attention—even if momentarily—back to the present moment. And just like that, and intriguingly so, sculptures sans pragmatic functions can morph into beacons of positivity—an escape into an ever-evolving realm of unmoored expression. Reiterating this utopian potential, this ongoing exhibition brings to light a striking—sometimes garish—an ensemble that vacillates between recognition and familiarity, nestled at the crossroads of utility and futility.

191st of the MATRIX

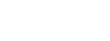

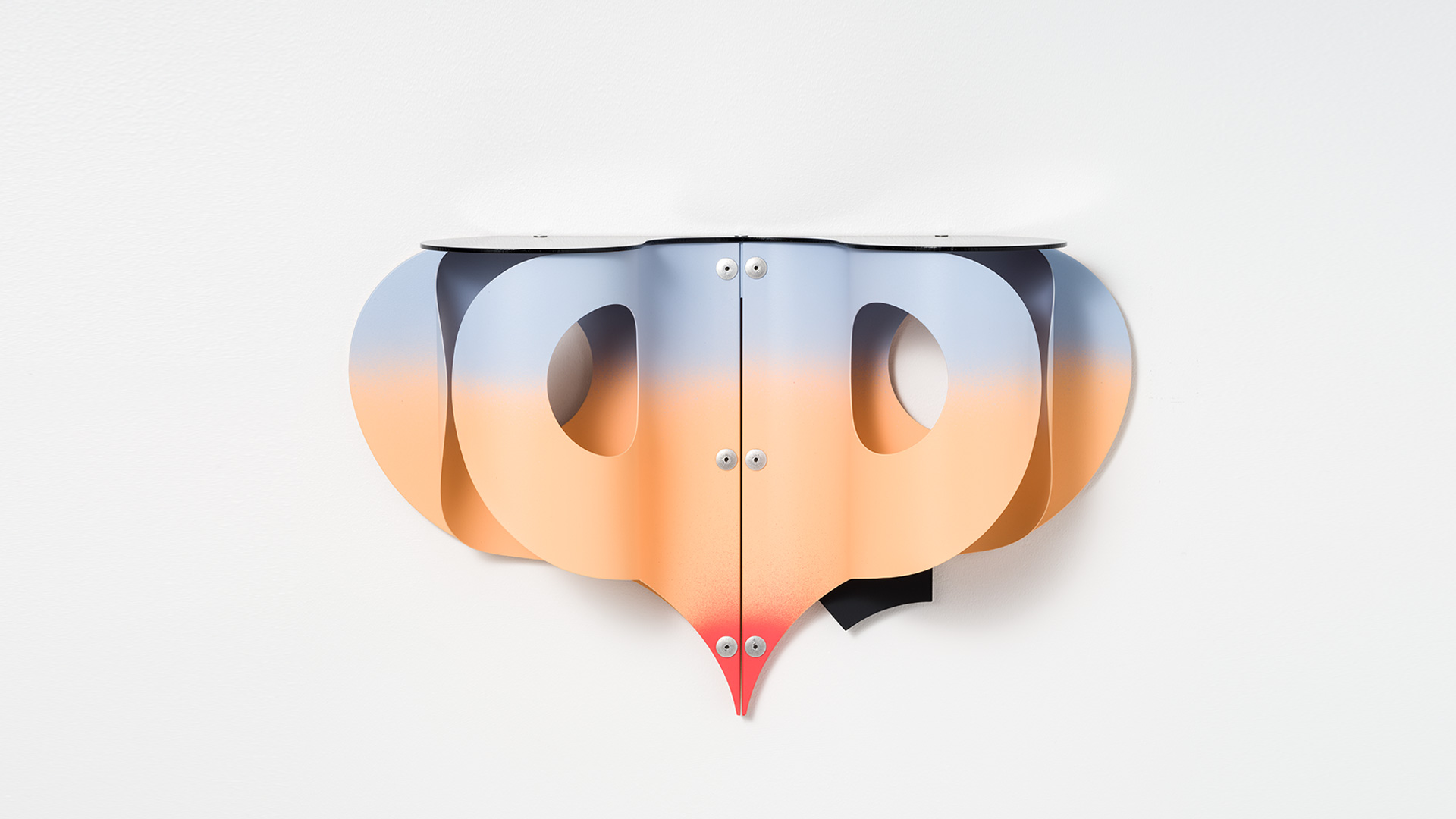

In his first solo museum exhibition, Los Angeles-based artist Matt Paweski unveils his latest body of work in an immersive installation where architecture, furniture and interior design fuse together. Matt Paweski / MATRIX 191, the artist's most ambitious presentation to date joins the nearly 50-year history of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art's MATRIX series, a chain of exhibitions by emerging artists that encourage exploration of their practice. In the solo exhibition on view from February 3 to May 7, 2023, , Paweski bedecks the space with a group of modestly scaled tabletop and wall-mounted sculptures, all made specifically for the Connecticut-based museum. With works seeming to reference domestic objects like clocks, shelves, baskets and mirrors, the exhibition space encompasses functional objects such as chair designs and pendant lamps, as well as tables that have lost utility owing to sculptures embedded into their surfaces.

Artworks and design objects intermingle in a fluid exploration of the realm between the utilitarian and the ineffectual. "Paweski’s awareness of history and context, coupled with the singularity of his aesthetic, make him a true embodiment of the spirit of MATRIX,” says Jared Quinton, Interim curator of contemporary art at the Wadsworth. “With their intensity of line, colour, and craftsmanship, his sculptures are like compact bundles of energy waiting to be unleashed,” he adds.

Moving on—and away—from predictability

Born in Detroit, Michigan, Paweski studied art at Arizona State University while working as an apprentice painter for a commercial fabrication shop simultaneously—experiencing art and fabrication in tandem. Following his graduate studies, he shaped his singular sculptural lexicon in a process of continuous evolution and expansion. Though his strides are not necessarily towards refinement; when things become too tasteful or predictable, Paweski has a tendency to move on. The formalist abstract works, mostly made from painted aluminium, often look functional, alluding to industrial design and furniture design. Yet they originate from an intuitive, manual process of drawing, cutting, shaping, painting, reconfiguration, and experimentation—a journey reverent towards craftsmanship wherein every crisp edge or matte surface is finished by the artist’s hand. “Their greatest power lies, however, in the ambiguity they are able to sustain. In a world overrun with standard design, material waste, and visual information, these works function like modest proposals, prompts for questioning, or catalysts for reflection. They draw us in with their formal beauty and strangeness, then send us back into the world looking for answers,” states Quinton.

An elusive stillness and a transient encounter with your physicality

Within the walls of the gallery, Paweski conceives his interpretation of a museological display or perhaps even the Gesamtkunstwerk (a historical German term for a work of art that unites many different art forms in a singular scheme) with a series of premeditated interventions. Levitating walls become demarcations in the otherwise oblong room, creating domestically scaled environments to experience his works more intimately. A twelve-inch aqua green border trails the architecture of the space, including doors, windows and air vents. Wall-mounted sculptures, artist-made chairs and four identically scaled pedestals containing one small freestanding sculpture are carefully interspersed in the gallery while a cluster of eight sculptural pendant lights illuminates the room. “It seems that in such a hyper-technological world, so much of what makes our lives possible is invisible and unseen, taken for granted daily,” Paweski says. “The sculptures are ... an anchor or trap to catch someone, give them pause, and focus them back on their own physicality, even if for just a second. A service interrupted that leads to something greater. There is a positivity to the uselessness of the sculpture,” he adds.

Contriving an alien familiarity

Buttons, cranks, levers, or hinges amalgamate with diluted lines, sliced metal planes, and theatrical colours in a language of machine-like silhouettes that are vaguely familiar yet idiosyncratic. Some of the works seem to draw from industrial product design—perhaps meat slicers, Lite-Brites, or circuit boards—while others have more art historical influence, evocative of iconic minimalist sculptures or technology-inspired modernist paintings. The pieces that make a resounding statement are two bizarre, most “difficult” artworks: Vessel (Butter) and Bonnet (Shaker). Featuring traditional scales and proportions of plywood finished with immaculate coatings of green and yellow enamel paint, the surfaces of the table designs are embedded with aluminium sculptures. These obscure compositions of slits and curves cut into the supports, slicing deep into the surfaces and impeding their functioning.

The wall and pedestal-mounted sculptural art, although aligning with Paweski’s oeuvre, exude novelty through animalian forms and contrasting colours and gradients. “The works remain familiar and relatable to the experiences I have had. They are objects we have used or interacted with or memories of places we have been. But at the same moment, they are totally alien, only really relatable to the other sculptures they are born from and the language they have created,” the sculptor shares.

Forward-looking details with glimpses of history

Paweski’s creative expedition propelled ahead by fastidious craftsmanship and attention to detail is reminiscent of a number of historical traditions and practitioners. One important source of inspiration is the Shakers, the separatist Christian sect dating back to the 18th century known dominantly for their furniture and handicrafts. Serving as material expressions of their beliefs, each work underlined form over function (a Shaker axiom goes “Beauty rests on utility”). Scottish artist, architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Swiss-French interior designer Janette Laverrière also bolster Paweski’s work. The American artist views their interdisciplinary practices as archetypes for juxtaposing art, design, utility, and formal invention. Both creatives enunciated an unwavering belief in the fluidity of form and function—a fluidity that vivifies Paweski’s practice today.

“Delusional utopia”

In the interconnected web of references that the sculptures weave around the viewer, images of both the outside world and the works themselves dialogue. Some recall miniature architectural maquettes or esoteric monuments, establishing harmony despite the adjacency of contrasting palettes, visual weight, and surface finish. Small knots of wave-like metal curves mirror robotised flora or fauna while small pieces of black-painted metal adorn the works and infringe their symmetry. In the lamp designs and shelf-like works, ornamental forms of the other sculptures are repurposed as structural supports. “I would say that I live in a kind of delusional utopia, and the work carries those traits,” Paweski explains. “The objects are very optimistic. I expect a lot from what I make, and I assume that people will find all the secrets and draw the connections,” he adds.

Matt Paweski / MATRIX 191 will be on display from February 3 to May 7, 2023, at Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut.

Sign in with email

Sign in with email

What do you think?